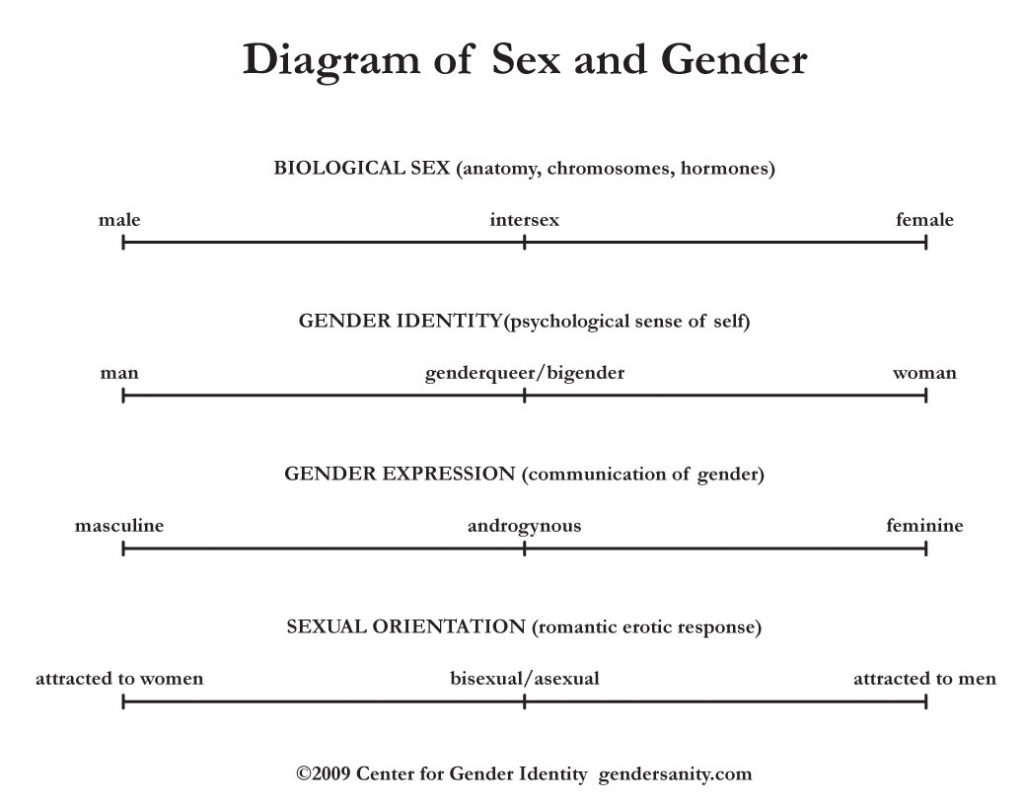

Biological sex, shown on the top scale, includes external genitalia, internal reproductive structures, chromosomes, hormone levels, and secondary sex characteristics such as breasts, facial and body hair, and fat distribution. These characteristics are objective in that they can be seen and measured (with appropriate technology). The scale consists not just of two categories (male and female) but is actually a continuum, with most people existing somewhere near one end or the other. The space more in the middle is occupied by intersex people (formerly, hermaphrodites), who have combinations of characteristics typical of males and those typical of females, such as both a testis and an ovary, or XY chromosomes (the usual male pattern) and a vagina, or they may have features that are not completely male or completely female, such as an organ that could be thought of as a small penis or a large clitoris, or an XXY chromosomal pattern. Gender identity is how people think of themselves and identify in terms of sex (man, woman, boy, girl). Gender identity is a psychological quality; unlike biological sex, it can’t be observed or measured (at least by current means), only reported by the individual. Like biological sex, it consists of more than two categories, and there’s space in the middle for those who identify as a third gender, both (two-spirit), or neither. We lack language for this intermediate position because everyone in our culture is supposed to identify unequivocally with one of the two extreme categories. In fact, many people feel that they have masculine and feminine aspects of their psyches, and some people, fearing that they do, seek to purge themselves of one or the other by acting in exaggerated sex-stereotyped ways.

Gender expression is everything we do that communicates our sex/gender to others: clothing, hair styles, mannerisms, way of speaking, roles we take in interactions, etc. This communication may be purposeful or accidental. It could also be called social gender because it relates to interactions between people. Trappings of one gender or the other may be forced on us as children or by dress codes at school or work. Gender expression is a continuum, with feminine at one end and masculine at the other. In between are gender expressions that are androgynous (neither masculine nor feminine) and those that combine elements of the two (sometimes called gender bending). Gender expression can vary for an individual from day to day or in different situations, but most people can identify a range on the scale where they feel the most comfortable. Some people are comfortable with a wider range of gender expression than others. Sexual orientation indicates who we are erotically attracted to. The ends of this scale are labeled “attracted to women” and “attracted to men,” rather than “homosexual” and “heterosexual,” to avoid confusion as we discuss the concepts of sex and gender. In the mid-range is bisexuality; there are also people who are asexual (attracted to neither men nor women). We tend to think of most people as falling into one of the two extreme categories (attracted to women or attracted to men), whether they are straight or gay, with only a small minority clustering around the bisexual middle. However, Kinsey’s studies showed that most people are in fact not at one extreme of this continuum or the other, but occupy some position between. For each scale, the popular notion that there are two distinct categories, with everyone falling neatly into one or the other, is a social construction. The real world (Nature, if you will) does not observe these boundaries. If we look at what actually exists, we see that there is middle ground. To be sure, most people fall near one end of the scale or the other, but very few people are actually at the extreme ends, and there are people at every point along the continuum.

Gender identity and sexual orientation are resistant to change. Although we don’t yet have definitive answers to whether these are the result of biological influences, psychological ones, or both, we do know that they are established very early in life, possibly prenatally, and there are no methods that have been proven effective for changing either of these. Some factors that make up biological sex can be changed, with more or less difficulty. These changes are not limited to people who change their sex: many women undergo breast enlargement, which moves them toward the extreme female end of the scale, and men have penile enlargements to enhance their maleness, for example.

Gender expression is quite flexible for some people and more rigid for others. Most people feel strongly about expressing themselves in a way that’s consistent with their inner gender identity and experience discomfort when they’re not allowed to do so. The four scales are independent. Our cultural expectation is that men occupy the extreme left ends of all four scales (male, man, masculine, attracted to women) and women occupy the right ends. But a person with male anatomy could be attracted to men (gay man), or could have a gender identity of “woman” (transsexual), or could have a feminine gender expression on occasion (crossdresser). A person with female anatomy could identify as a woman, have a somewhat masculine gender expression, and be attracted to women (butch lesbian). It’s a mix-and-match world, and there are as many combinations as there are people who think about their gender. This schema is not necessarily “reality,” but it’s probably closer than the two-box system. Reality is undoubtedly more complex. Each of the four scales could be broken out into several scales. For instance, the sex scale could be expanded into separate scales for external genitalia, internal reproductive organs, hormone levels, chromosome patterns, and so forth. An individual would probably not fall on the same place on each of these. “Biological sex” is a summary of scores for several variables. There are conditions that exist that don’t fit anywhere on a continuum: some people have neither the XX (typical female) chromosomal pattern nor the XY pattern typical of males, but it is not clear that other patterns, such as just X, belong anywhere on the scale between XX and XY. Furthermore, the scales may not be entirely separate: if gender identity and sexual orientation are found to have a biological component, they may overlap with the biological sex scale. Using the model presented here is something like using a spectrum of colors to view the world, instead of only black and white. It doesn’t fully account for all the complex shadings that exist, but it gives us a richer, more interesting picture. Why look at the world in black and white (marred by a few troublesome shades of gray) when there’s a whole rainbow out there?